1941: conscription for women was introduced

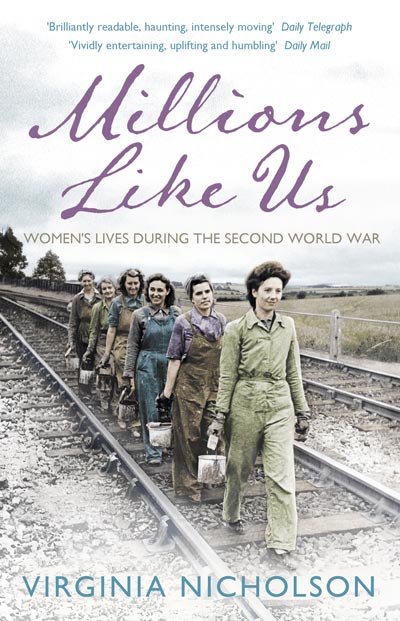

Millions Like Us

Women’s Lives during the Second World War

In 1939 most women still expected to become wives and mothers. The war years took the inferiority myth and destroyed it, catapulting servants and mistresses alike into a world of life and death responsibilities.

From 1941, in an unprecedented move, women were conscripted (though not to combatant duty). Uprooted, these women were now launched into new lives in the services and the war factories. They became nurses, code-breakers, ambulance drivers, entertainers, welders – and even pacifists. Emotionally, their lives were turned upside down by the effects of bereavement, the evacuation of children, homelessness, family break-ups, shotgun marriages, illegitimacy and divorce. But in conditions of “Total War” millions of women demonstrated that they were cleverer, more broad-minded and altogether more complex than anyone had ever guessed. A whole generation had awakened to their own potential. Deep down, they no longer bought the myth that women were inferior.

Then came peace. The nation’s wives appeared to be retreating to the comfort zone of home. At the same time family tensions were running high, and by 1947 divorce figures were topping 60,000.

But the women who went back were changed for ever. World War 2 had revolutionised their lives. Millions Like Us tracks women’s experiences of a momentous decade through a host of individual stories, drawing on autobiographies, archives and living memory. It tells of their pioneering contributions to our national story, of how they tried to re-make their world in peacetime, of how they loved, suffered, laughed, grieved and dared. And of how they would never be the same again…

I am available to promote Millions Like Us through appearances, interviews and articles.

For further information contact Amelia Fairney at Penguin amelia.fairney@uk.penguingroup.com

Vera Lynn

In 2009 Virginia Nicholson met and interviewed Dame Vera Lynn at her Sussex home. The veteran “Forces’ Sweetheart” talked to Virginia about her wartime singing career and her time in Burma with ENSA. In Millions Like Us, Virginia writes:

““Vera’s voice, and her songs had – and have – a uniquely affecting and patriotic quality which touched her listeners’ souls . Yet she herself recognises that it was her very ordinariness that stole her audiences’ hearts. In her nineties, this woman is still luminously beautiful, but the comfortable cardigan and clipped Cockney are the clues to Vera Lynn’s sweetness and approachability. The lads of the West Kents and the Durham Light Infantry, killing and dying in a rat-infested wilderness strewn with human remains, recognised her as a symbol of the world they were fighting for.” ”

Excerpts from Millions Like Us:

Excerpt 1

from Chapter 8 “Over There”, which includes the events of D-Day, May 1944:

In Portsmouth, teenager Naina Cox was working in a big dry-cleaning firm that dealt with service uniforms; she had just completed a Red Cross course that spring. At 2pm on D-Day she was summoned by her commandant to come up to Queen Alexandra's Hospital and help with casualties. Quickly, she ran home to tell her mum, scrambled into her uniform, and headed up the hill to the hospital. There she found the wards had run out of space; the corridors were lined with stretchers.

D-Day casualties, 1944

As an inexperienced junior, Naina was given the job of cleaning up the patients. Many were bloody and grimy, but fear had also struck at their bowels, resulting in fouled bodies and garments. For several days Naina washed the excrement from hundreds of traumatised soldiers.

"[They] were so completely exhausted they didn't care one jot what happened to them. As I worked I was thinking, 'How long will it go on? If I come tomorrow and the next day, will I still be doing this?'"

But she barely hesitated when the sister asked her to perform the same task on the German prisoners' ward. In a stinking Nissen hut, the terrifying enemy lay festering and utterly demoralised: dirty, unwholesome and glazed with defeat.

"Some of them were only kids, they weren't really much older than me. One of the rules of the Red Cross is that you are there to help everybody. I'm glad I didn't refuse to help those men."

During that terrible first week as the Allies battled to gain their foothold in France and German forces retaliated, planes were crashing on the Isle of Wight, and bodies were washed up on its pebbly shores. Sometimes Monica Littleboy accompanied stretcher cases across to the mainland hospital.

"I saw sights [there] which I hope I may, please God, never see again. They were burnt so badly as to be unrecognisable, only the burning eyes could one see, and as we loaded our stretchers I could feel those eyes following me round the ward. Something inside me just seemed horror struck."

Maureen Bolster was equally appalled when she met a shell-shocked lad just back from the fighting. He was trembling, and could barely speak.

"Poor kid, all he could say was, 'Make me forget it, please make me forget it. I've just got to.' I felt quite sick with pity. What that kid had seen was beyond telling. For one thing he had seen his special pals blown to pieces."

The reactions of Maureen Bolster, Monica Littleboy, Naina Cox, and many other women show the vulnerability of women exposed to war's horrors. Pity, compassion and distress at the pointlessness of human suffering are the emotions of an entire sex unhardened to inhumanity; more than that, a sex as indoctrinated with susceptibility as men have been with their stiff upper lips.

But for many of those soldiers, D-Day proved traumatic; seasick and terrified troops floundered up those beaches past the bodies of their drowned and dying comrades. And the wounded survivors of that bitter fight returned to have the unheroic shit swabbed off them by meek teenagers like Naina Cox.

Excerpt 2

from Chapter 11 “Picking Up the Threads” (about the end-of-war celebrations and demobilisation):

The war is over. A WAAF returns home.

As the homecomings began, parties were laid on for the returning servicemen. In Liverpool, as elsewhere in the country, communities welcomed them back with slap-up feasts. There was great baking and cutting of sandwiches. Helen Forrester couldn't help but feel bitter envy at the sight of happy wives, equipped with pails of whitewash, chalking the house walls with their husbands' names: WELCOME HOME JOEY. WELCOME HOME GEORGE. Harry O'Dwyer was one of 30,248 merchant seamen who would never come home to her. Eddie Parry was one of the 264,443 British servicemen who would never come home either. It struck her then that nobody ever painted messages for "the Marys, Margarets, Dorothys and Ellens, who also served. It was still a popular idea that women did not need things. They could make do. They could manage without, even without welcomes.”

In fact, many Marys, Ellens and Dorothys spent the next couple of months, or more, feeling jaded and impatient. WAAF driver Flo Mahony was in north Wales for the victory celebrations. There were, she recalls, some small bonfires. But more memorable to her is the sense of uncertainty and resentment:

“The war basically stopped. There was no more wartime flying. And so air crew were redundant and they didn't know what to do with them. So they sent them to the Motor Transport section and told them to go and be drivers – and of course that was our job. So there was quite a bit of resentment of these air crew. And a lot of people were at the end of their tether and were quick to flare up, and there were lots of frictions.”

Men and women alike chafed at the tin-pot bureaucracy and officiousness that now prevailed. Flo recalled:

"The Air Force was known for being relaxed compared to the army. But now there were so many people sitting about with not enough to do, and suddenly, you had to go on church parade, you had to do this, you had to do that. You had to be properly dressed. And they started making us do drill all over again."

There was work, but it seemed to have no purpose. Idle servicewomen – and men – were encouraged to attend Educational and Vocational Training classes to prepare them for civilian life. A future as a shorthand typist or counter clerk beckoned…

Gallery

Reviews

Bel Mooney, The Daily Mail

It's hard to single out stories from this rich, entwined narrative, which moves in and out of the lives of an absorbing cast of characters... Vividly entertaining, uplifting and humbling, Millions Like Us deserves to be a bestseller...

Reading her fascinating book introduces you to hundreds of wonderful women - a magnificent regiment - you wish you had met in the flesh, and when you close it you feel enlarged as well as amazed by their experiences...

Nicholson's achievement is to bestow honour where the women themselves would have seen only ordinariness. She throws a spotlight on the varied experiences of six million women, tracking their experiences over ten years - and leaving us in no doubt that these unsung heroines who worked tirelessly and suffered danger as well as deprivation played a vital role in helping to win the war...

•

Anne Chisholm, The Spectator

By tradition, 'What did you do in the war?' is a question children address to Daddy, not to Mummy. In this ambitious, humane and absorbing book Virginia Nicholson moves Mummy firmly to the centre of the stage as she chronicles, largely in their own words, the lives of British women during the second world war...

The range and detail of this account are a revelation... her research has been phenomenally thorough and her narrative control is equally impressive...

This is the third book in which Virginia Nicholson has demonstrated her belief that story and biography can be combined, that 'the personal and idiosyncratic reveal more about the past than the generic and comprehensive.'

As a way of rescuing human feeling and individual experience from the fossilisation of time and received opinion this book could not be better. I shall try to ensure my granddaughters read it.

•

Artemis Cooper, The Evening Standard

Her passionate engagement in the lives of those she follows, how they changed as the war progressed, drives the story forward and provides some fascinating insights...Nicholson is profoundly sympathetic to the way they retreated into their hearth-and-home mentality, while at the same time feeling that women lost a vital opportunity to shape the post-war world.

•

Edwina Currie, The Times

It's a joy that [these] memories are being rescued before it's too late... Where Nicholson scores over other histories and memoirs is that her vivid narrative is set firmly in the context of the time, which can seem so alien today as to be from another planet...

This lovely book is... poignant, hilarious and inspiring...

•

Kathryn Hughes, The Mail on Sunday

The joy of Virginia Nicholson's book is the way she has plaited scores of individual stories into a richly textured account of the many forms that female courage can take... Using evidence from diaries, letters and memoirs, Virginia Nicholson has stitched together a deeply moving account of female courage both at home and overseas during those six brutal years...

[She] is keen to offer us much more than a series of chirpy anecdotes. Instead she argues that the war years, poised halfway between the suffragettes and women's lib, were a crucial staging post in the development of modern feminism...

This story belongs to us all.

•

Sinclair Mackay, Daily Telegraph

Virginia Nicholson's brilliantly readable, often haunting history of the war...

With this sharply written and intensely moving book, Virginia Nicholson has paid [this generation] proud tribute.

•

Lucy Lethbridge, Observer

Reading Nicholson's account of their experiences, one can only marvel at the inner resources of a generation that disapproved of introspection... Nicholson's brisk prose style moves the narrative on, but it is the writing of the women themselves that astonishes...

Millions Like Us is a tremendous achievement. It is a triumph of research and organisation - but also of sympathy.

*

Christopher Silvester, Daily Express

As with her previous book Singled Out... Nicholson has done prodigious research. By adopting the same approach of collective biography she is able to present the story with profound empathy as well as insight... It is in this key respect that Nicholson's technique of weaving together individual stories works so well...

This is a magnificent work of social history, written with passion and panache, in which Nicholson convincingly fulfils her own requirement to "get under the skins of the people who made it: our mothers, our aunts, our grandmothers".

*

Juliet Gardiner, Literary Review

What Nicholson has done with great aplomb is tell the story of the Second World War through the optic of women's lives... a richly polyphonic story extraordinarily well told... Millions like us, yet all very different: their story has rarely been more evocatively told.

•

Julie Summers, The Sunday Times

With a huge cast of characters, Nicholson's history gives a vibrant portrait of a society turned upside down by the wholesale deployment of men and women.